Investor Protection? Never Heard of It. Analysis of Top ICOs

The vast majority of initial coin offering (ICO) projects promising, for example, team token vesting periods or no additional tokens minted after the ICO have no code in their smart contracts to keep those promises, a study finds. Of the top 50 projects that the team analyzed, only 10 of them actually contained all of the relevant code in their contracts.

The new legal paper, titled “Coin-Operated Capitalism” and released by a team from the University of Pennsylvania School of Law shows how the world of ICOs has grown in the past year and a half. Claiming to be “the legal literature’s first detailed analysis of the inner workings of Initial Coin Offerings,” the study collected 50 top-grossing ICOs of 2017, and analyzed how the software code controlling the projects’ ICOs reflected their contractual promises: “Many ICOs failed even to promise that they would protect investors against insider self-dealing.”

“One take-home is that no one reads smart contracts, making them a rickety wheel on the ICO investment vehicle,” says the paper. It continues that, “minted crypto asset is created through an act of founder fiat [a formal authorization or proposition; a decree].”

According to the study, “if ICO investors were scrutinizing smart contract code before buying into an ICO, we would expect to see (all else equal) higher capital raises by teams that faithfully coded supply and vesting protections, and also disclosed their modification powers.”

“We find no evidence of that effect in our sample,” the team concluded.

They continue that “Surprisingly, in a community known for espousing a technolibertarian belief in the power of “trustless trust” built with carefully designed code, a significant fraction of issuers retained centralized control through previously undisclosed code permitting modification of the entities’ governing structures.”

Dave Hoffman, professor of law at the University of Pennsylvania, who also contributed to the research, tweeted:

Another problem is founder desertion – where teams launch an ICO and then quickly dump all of their tokens onto the market as soon as possible. This is why vesting periods exist, which means people holding the tokens cannot sell them until a certain date or amount of time has passed. However, most ICOs that promise vesting periods do not include a code for that either, the study found.

“The fact that 37 of the leading ICOs—each of which raised over USD 20 million—fail to write their own vesting promises into code is inconsistent with a story about code replacing law. It also raises serious questions about whether investors are adequately protected from founder desertion,” the study warns.

The authors have created something called the paper-code distance: the difference between the whitepaper promises and the smart contract reality, rated between 0 and 4. 0 means the code reflects the promises of the paper completely, whereas 4 means there are significant differences between what was promised, and what was coded.

“Of the 50 ICOs, 10 (20%) have no distance, 30 (60%) have one, 8 (16%) have two, 1 (2%) had three, and 1 (2%) has four,” it reads, going on to remind readers that there are very few legal protections available for ICO investors in the event that promises made by the team are not kept.

It concludes that lawyers and other legal representatives will need more knowledge about the matter going forward. “Traditional, paperbound lawyers are not going extinct, but we may be witnessing the emergence of a new form of transactional technology that will drastically alter how they do their jobs,” it says, explaining that the rise of ICOs will need to be accompanied by enforceable regulations.

____________

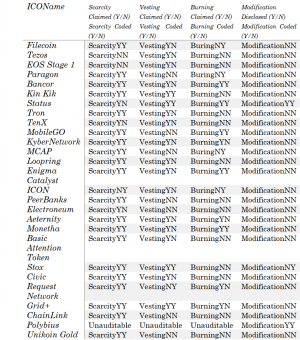

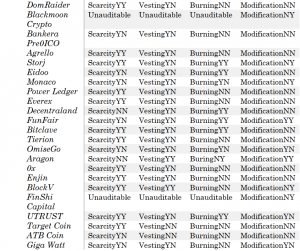

Below is the summary of code/contract audit, published in the study: