Stablecoins are the new black, but just how stable are they?

Pegging to USD is more of a target than a guaranteed method of keeping a currency’s value absolutely fixed.

It’s no secret that bitcoin and many other cryptocurrencies aren’t particularly stable. Having topped USD 19,000 on December 17, bitcoin hit a low of c. USD 6,000 on February 6 and now trades c. USD 10,000 again, with investors and the public alike wondering whether it will ever be suited to everyday use as a currency.

They’re not the only ones who’ve been wondering, since an increasing number of companies and startups have begun offering a new kind of cryptocurrency: stablecoins.

These are cryptocurrencies that peg their value to one US dollar, so that holders can actually afford to use them for day-to-day transactions. Just like other cryptocurrencies they run on decentralised blockchains and use anonymised wallets, yet the companies behind them use a variety of systems, market algorithms and trading incentives in order to keep their values as close as possible to one US dollar.

Yet the question is, just how stable are stablecoins?

Tether story

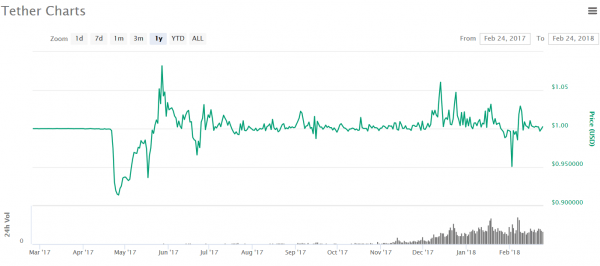

If we were to look at the most well-known example – tether – then the answer might be, ‘not very much.’ Tether (or USDT) was launched in 2015, with the leaked Paradise Papers revealing that the owners of the company behind it also own the Bitfinex crypto exchange.

Its pegging to USD 1 makes it important for traders using exchanges that don’t offer trading pairs in a fiat currency such as the US dollar. That’s because its (nominally) stable value means they can quickly cash out of risky positions with other cryptocurrencies and wait for a more favourable period to reinvest in, say, bitcoin or litecoin.

The thing is, there really is no systematic mechanism operated by the Tether company to ensure that each USDT really is worth one US dollar. The company reportedly has its own reserves of US dollars (and of euros), from which it could pay all those who own tether. However, while its website claims its “reserve account is regularly audited,” it split with its auditors – Friedman LLP – on January 27, before a full audit could ever be completed. This break has fuelled rumours that its reserves aren’t large enough to cover all the USDT currently in circulation, which currently stand at a hefty USD 2.35 billion.

And given that it’s stated on Tether’s own website that the company “must and does at all times reserve the right to refuse to issue or redeem Tether Tokens,” it’s perhaps becoming increasingly naive to think that tether really is a ‘stable’ cryptocurrency.

Newcomers

Despite these fears, new stablecoins have been emerging in recent months, all of which promise to offer stability while being more transparent than tether. One of the most recent is trueUSD, which was launched on January 24 by Californian startup TrustToken. It works in essentially the same way as tether, with one trueUSD token worth one US dollar, and with TrustToken holding the corresponding USD reserves in custodial bank accounts. The main difference, however, is that token holders are awarded “legally protected certificates of ownership of US dollars.”

This legal protection, coupled with “monthly professional audits,” has attracted such investors in trueUSD as BlockTower Capital, FJ Labs, and Stanford-StartX. Speaking of the promise shown by the cryptocurrency, BlockTower Capital’s co-founder, Ari Paul, said, “I’ve eagerly awaited the launch of a transparent and regulatory compliant stablecoin. TrueUSD will make it easier for us to trade cryptocurrency across exchanges.”

A similarly optimistic future is hoped for by the creators of dai, a stablecoin that was launched on December 18 by another Californian startup, MakerDAO. In contrast to TrueUSD and tether, dai’s value (1 dai = 1 USD) is maintained through a decentralised, autonomous system. Users obtain dai by depositing ether (ETH)as collateral, and should dai ever rise above or fall below USD 1, the Dai Stablecoin System engages its automatic “Target Rate Feedback Mechanism” in order to fix the imbalance.

In theory, this complex framework makes dai more stable and secure than tether or TrueUSD. However, dai dropped in value by around 30% within two weeks of launching, temporarily hitting a low of USD 0.72 on January 11. It quickly recovered, although casual observers may be curious as to how it could have possibly dipped by even USD 0.01 against the dollar, given that it’s supposed to be ‘pegged’ to USD 1.

Not a guarantee

Well, in the case of stablecoins and fiat currencies alike, pegging is more of a target than a guaranteed method of keeping a currency’s value absolutely fixed. And it can never be a guarantee, since pegged currencies are usually traded on an open market, meaning that institutions or companies trying to keep their values fixed to a peg always have to contend with players who want to make a profit out of trading them above or below their target prices.

Yet more seriously for dai, some critics have claimed that its reliance on ETH as collateral makes it vulnerable in scenarios where the value of ETH significantly decreases. One of these critics was Havven, a Sydney-based company which launched an expression of interest period on January 8 for its own stablecoin. Named the nomin (nUSD), its pegged value will be backed up (collateralised) by another Havven cryptocurrency, appropriately dubbed the havven.

Seeing as how neither of these have been launched yet, it’s still too early to tell whether Havven’s platform will have similar vulnerabilities as that of MakerDAO’s. However, Havven’s system requires 80% of the havven tokens in existence to be preserved as collateral for the nUSD stablecoin, potentially giving nUSDs stronger protection against a dive in the value of havvens.

The key word here is “potentially,” since past stablecoins – e.g. bitshares (bitUSD) – haven’t been 100% stable, and neither have they really been tested by high volume trading. Nonetheless, as shown by the recent emergence of trueUSD, dai, nUSD, and now also basecoin, there are enough new entrants in the field who believe they have the ingredients needed to produce a commercially viable stablecoin. Only time will tell whether they’re right.